The first half of 2019 was a drama involving the bond market anticipating a recession and the stock market assuming that the Fed would ride to the rescue by pushing interest rates lower. The Fed indicated a rate cut would be prudent to ensure continued economic growth; stocks continued to rally while bond holders remained wary of recession risks.

Through June 30, 2019 (if MCS clients’ investments were treated as one large portfolio including their cash), on average clients gained 3.34%1, after fees. For comparison purposes, the S&P 500 Total Return Stock Index (S&P 500) gained 18.54%, and the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index gained 6.11%. The range of MCS individual client returns was from a gain of 0.80 % to a gain of 7.25%. MCS results represent the downside of a defensive strategy; you don’t make as much as investors that took more risk. If that leaves you frustrated, let’s have a conversation; it’s easy to get more exposure to stocks.

As a money manager, a key part of my job is reading, reading and more reading to understand the world and what others think about it, and then to use that information to make the best investment decisions for my clients. I look for harbinger articles: articles that may have significant future implications but are currently an emerging or under-appreciated aspect in the economy or investments. Economic research reports play an important role in comparing the past and present trends and their future implications. This newsletter quotes liberally from these sources. I think it’s important for you to know that my concerns are shared and expanded upon by some of the world’s top investment managers. I feel that having concepts explained in a different way by someone else is conducive to better understanding.

In this newsletter, I’ll offer a summary of and comments on some of the best infor mation I’ve come across.

The Experts Don’t Agree… Even Within the Same Firm

I am a long-time subscriber to the Bank Credit Analyst (BCA), an investment newsletter that starts at around $20,000 per year. This independent economic research firm is like hiring a team of economists. Their work is very high quality.

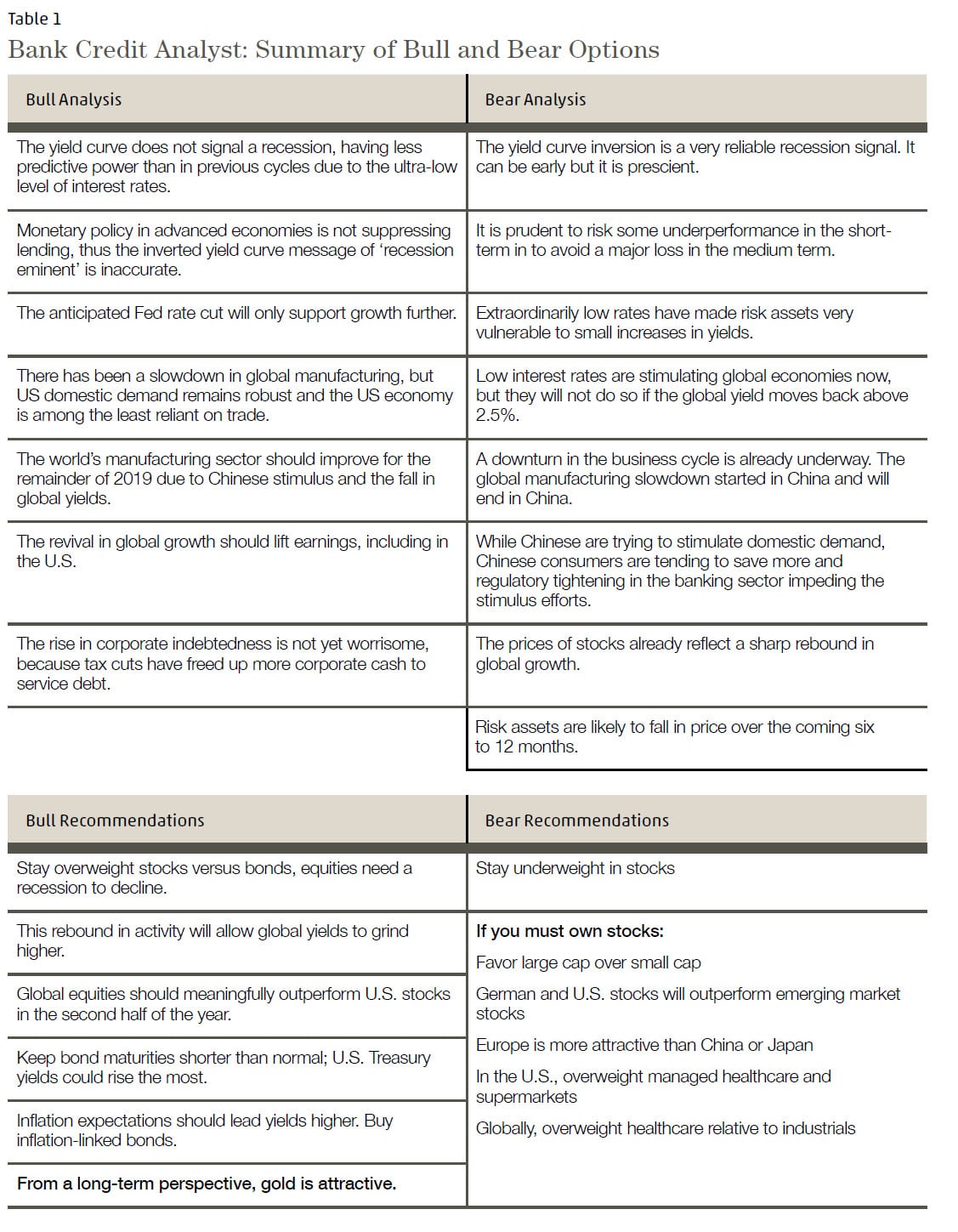

This week, BCA published an overview of the diverging opinions within their organization about the direction of the global economy and their corresponding financial market recommendations. Table 1 below lists an edited summary of their positions. The lack of a clear consensus within this important economic research firm is indicative of the investment decision challenges in the current environment.

I have highlighted their recommendation on gold, which will be discussed later in this newsletter.

Comments from Other Asset Managers Supporting and Informing Our Investment Strategy

A Bloomberg article on 06/20/2019, “Bull Markets Saved, Central Banks Now Risk an Investor Backlash2,” highlights my concern about how low the world’s central banks have pushed interest rates. Other institutional investors also fear that Central banks have little or no room to lower interest rates further to rescue economies from the next downturn. The article’s authors, Ksenia Galouchko and David Goodman, state: Their fear is that fresh stimulus, in the form of cheaper credit or even further bond-buying, won’t be enough to spark an uptick in chronically low inflation. Instead, it risks pumping up already pricey assets, potentially creating bubbles along the way.

“This reliance on central banks will take its toll on investors that take too much risk with their portfolios,” said Paul Flood, a multi-asset fund manager at Newton Investment Management, which oversees about 50 billion British pounds ($63 billion). “This will be a huge policy error that’s led to huge unintended consequences.”

The fear is that a US deflationary cycle could set in, similar to Japan’s since 1990. In essence, if the Fed halves interest rates from 2.5% to 1.25%, it will not have the same simulative economic impact as lowering interest rates from 5% to 2.5%. Stock market gains are increasingly based on financial engineering; relying on ultra-low interest rates and stock buybacks rather than improved company performance. Negative yields are designed to force borrowers out of safe assets by penalizing them for being conservative. Institutional investors see the potential for

a very bad ending to this cycle. Galouchko and Goodman continue: The upshot is not all investors think policy makers have the ammunition to spur price growth laid low by the economic fallout of the financial crisis and still hobbled by structural obstacles like aging populations and rising debt.

Another Bloomberg article warns about the lack of liquidity in many investments. In “Liquidity and a ‘Lie’: Funds Confront $30 Trillion Wall of Worry.3” Annie Massa and Craig Torres write: …the head of the Bank of England warned that funds pushing into a host of risky investments — in some cases, without investors fully understanding the dangers — have been “built on a lie.’’ Then the central banker, Mark Carney, spoke a word few policymakers use lightly: “systemic’’ — central bank-speak for the kind of risks that can cascade through markets, institutions and economies. Some $30 trillion is tied up in difficult-to trade investments, he noted earlier this year. The Federal Reserve highlighted liquidity risk in bond and loan mutual funds in its May financial stability report, noting that bank loan funds purchase a full fifth of newly originated leveraged loans. “The mismatch between these mutual funds’ promise of daily redemptions and the longer time required to sell bonds or loans may be heightened if liquidity in these markets diminishes in times of stress,” the report said.

Liquidity is the ability to buy/sell at low cost and in high volume. I have written earlier about the liquidity risks in bond funds and the bond market. Liquidity risk becomes an issue in the same way that “Fire!” being yelled in a crowded theatre does; people get hurt trying to exit a bad situation. I routinely get emails or calls pitching investment products called ‘Liquid Alts’4. I believe the term ‘Liquid Alts’ is an oxymoron; the liquidity only exists if the market remains orderly.

Investment crises often start in the less liquid areas of the economy and quickly ripple their way into the more liquid financial markets. For example, the 2008 Great Recession investment crisis was triggered by a failure of the credit default swap, an alternative investment.

The final article I will mention here, Paradigm Shifts5, was written by Ray Dalio, Co-Chief Investment Officer & Co-Chairman of Bridgewater Associates, L.P. one of the world’s most successful hedge funds. It is a long article, and I encourage you to read it in its entirety.

In this article, Dalio expounds in detail on a long-held investment philosophy of mine – what starts out as a reasonable investment thesis eventually gives way to pure folly that must be understood and acted upon early to protect my clients’ wealth. Dalio calls these periods “paradigms”. For those of you who have been with MCS for more than 20 years, you will remember how I negotiated the Tech Bubble and the Great Recession investment crises. I believe we are at risk of another such crisis, and Dalio does an excellent j ob of describing it.

Dalio writes: One of my investment principles is…Identify the paradigm you’re in, examine if and how it is unsustainable, and visualize how the paradigm shift will transpire when that which is unsustainable stops. … In paradigm shifts, most people get caught overextended doing something overly popular and get really hurt. There are always big unsustainable forces that drive the paradigm. They go on long enough for people to believe that they will never end even though they obviously must end. A classic one of those is an unsustainable rate of debt growth that supports the buying of investment assets; it drives asset prices up, which leads people to believe that borrowing and buying those investment assets is a good thing to do. But it can’t go on forever because the entities borrowing and buying those assets will run out of borrowing capacity while the debt service costs rise relative to their incomes by amounts that squeeze their cash flows. Another classic example that comes to mind is that extended periods of low volatility tend to lead to high volatility because people adapt to that low volatility, which leads them to do things (like borrow more money than they would borrow if volatility was greater) that expose them to more volatility, which prompts a self-reinforcing pickup in volatility.

Both high debt issuance in the corporate and government sectors and an extended period of low volatility exist now.

Dalio continues his article by proposing how the next paradigm shift might occur: While I’m not sure exactly when or how the paradigm shift will occur, I will share my thoughts about it. I think that it is highly likely that sometime in the next few years, 1) cen tral banks will run out of stimulant to boost the markets and the economy when the economy is weak, and 2) there will be an enormous amount of debt and non-debt liabilities (e.g., pension and healthcare) that will increasingly be coming due and won’t be able to be funded with assets… Said differently, I think that the paradigm that we are in will most likely end when a) real interest rate returns are pushed so low that investors holding the debt won’t want to hold it and will start to move to something they think is better and b) simultaneously, the large need for money to fund liabilities will contribute to the “big squeeze.”

Like the Galouchko and Goodman article I quoted earlier, Dalio is saying that lower interest rates will stop working as a ‘go to’ solution to keep the global economies growing. At the same time, more debt will need to be sold to address increasing social liabilities like pensions and healthcare. The “big squeeze” is the mismatch between the need for more borrowing and the willingness of investors to lend. These situations are headline grabbing and chaotic. Mr. Dalio continues: My guess is that bonds will provide bad real and nominal returns for those who hold them, but not lead to significant price declines and higher interest rates because I think that it is most likely that central banks will buy more of them to hold interest rates down and keep prices up. In other words, I suspect that the new paradigm will be characterized by large debt monetizations that will be most similar to those that occurred in the 1940s war years.

Here Mr. Dalio and I disagree. He suspects that bonds will experience modest losses, but interest rates won’t spike (creating large losses) as a result of these reflationary policies, the central bank will hold rates down by buying bonds. He references the 1940’s war years as an example of when this last occurred. This is certainly a possible outcome, however, I have serious concerns about this analysis. In the 1940s investors were favorably predisposed to buying bonds because:

Government bond investors survived the Depression with their wealth intact (unlike stock and real estate investors), and

there was a very high level of social cohesion in the US because of the war. We were all pulling together to address an existential threat to democracy. Sacrifices had to be made and buying war bonds was a patriotic duty. That social cohesion and level of trust in the gover nment does not exist today.

In our current, less socially cohesive environment, investors may avoid buying more and more long-term bonds that yield nothing to pay for those liabilities. If investors don’t buy the bonds, government(s) will be forced to:

print money to buy the bonds,

attempt to depreciate their currency, and/or

increase taxes to pay for growing liabilities.

An alternative outcome to these events is higher than expected inflation, which reduces the cost of debt in real terms. The cost of debt is reduced because the bond payments are fixed, and interest and principal received in the future have less purchasing power. Higher than expected inflation could a mean significant increase in interest rates, assuming the Fed executes on its mandate to keep inflation around 2%. Such an interest rate increase would pull the rug out from under stock, bond, and real estate prices.

In either Mr Dalio’s outcome or mine, his investment recommendation is worth considering: …those (investments) that will most likely do best will be those that do well when the value of money is being depreciated and domestic and international conflicts are significant, such as gold.

Wait, Aren’t Stocks an Inflation Hedge?

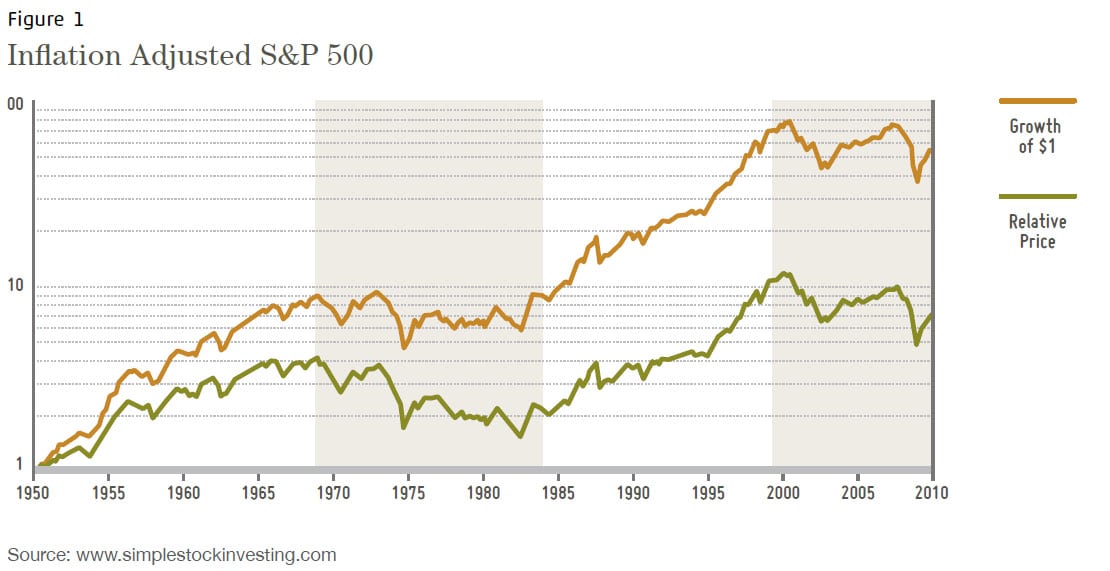

Stock investors have heard for years that stocks are a great inflation hedge. As a result, advisers and the financial press assure investors that owning stocks will protect them from inflation. Well, that’s true a lot of the time but not always. Stocks do terribly when inflation jumps unexpectedly and persists. As you can see in Figure 1, the high inflation environment of the 1970s produced dismal stock market returns, with the inflation adjusted return staying flat for almost 20 years from late 1968 until 1985 and again from 1999 to 2013. Stocks do exceptionally well when inflation is modest or declining.

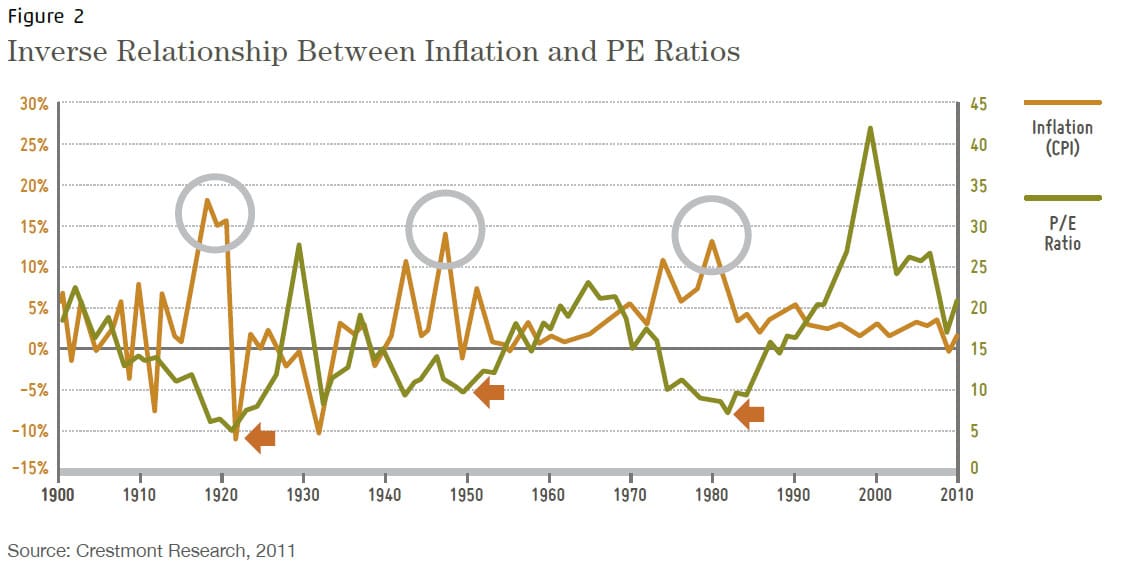

The reason the data looks so favorable for US stocks vs inflation is because the data contains few high inflationary periods. During the Inflationary period itself, stock PE ratios can collapse, lowering stock prices significantly. Therefore, while stocks beat inflation in the long run, stocks get beat up during higher than expected inflationary periods. The circles and arrows in Figure 2 denote these very bad times for stocks.

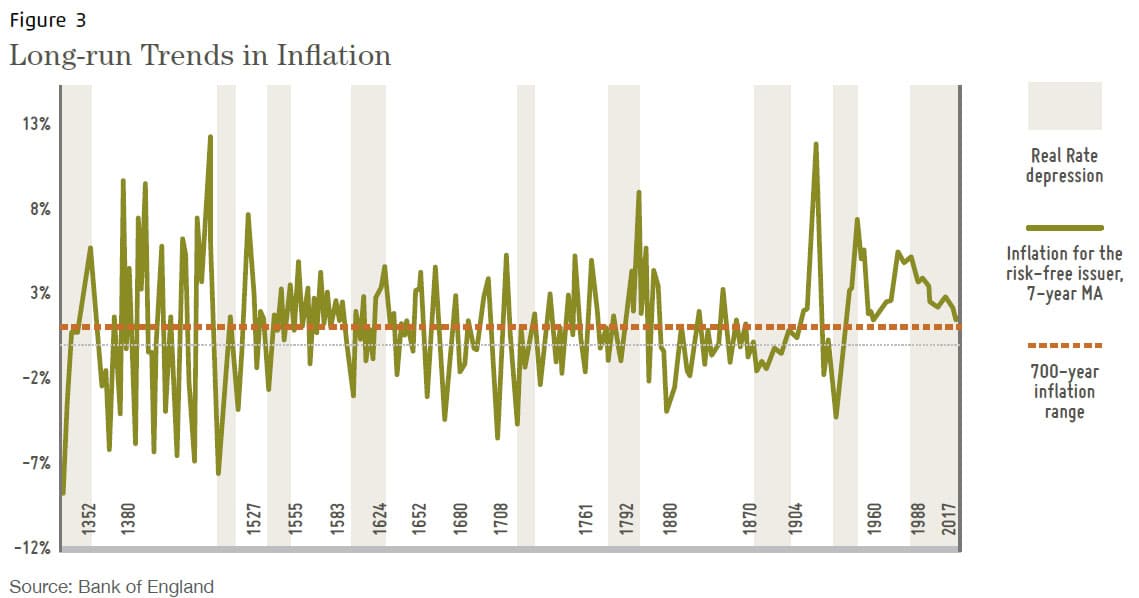

Given that most of the investment community believes that inflation is not a threat, my view is that a much lower rate of inflation surprise (e.g. 2.50 to 3.00%) would be enough to cause PE’s to contract and prices to drop. The final article I will reference is this gem penned in November 2017 by Paul Schmelzing, a visiting scholar at the Bank of England from Harvard University. In “Global Real Interest Rates since 1311: Renaissance Roots and Rapid Reversals6,” he gives us a true long-term view. Although global inflation averaged at 1.09% over a 700-year period (much lower than I would have guessed), there is a ton of volatility around that average.

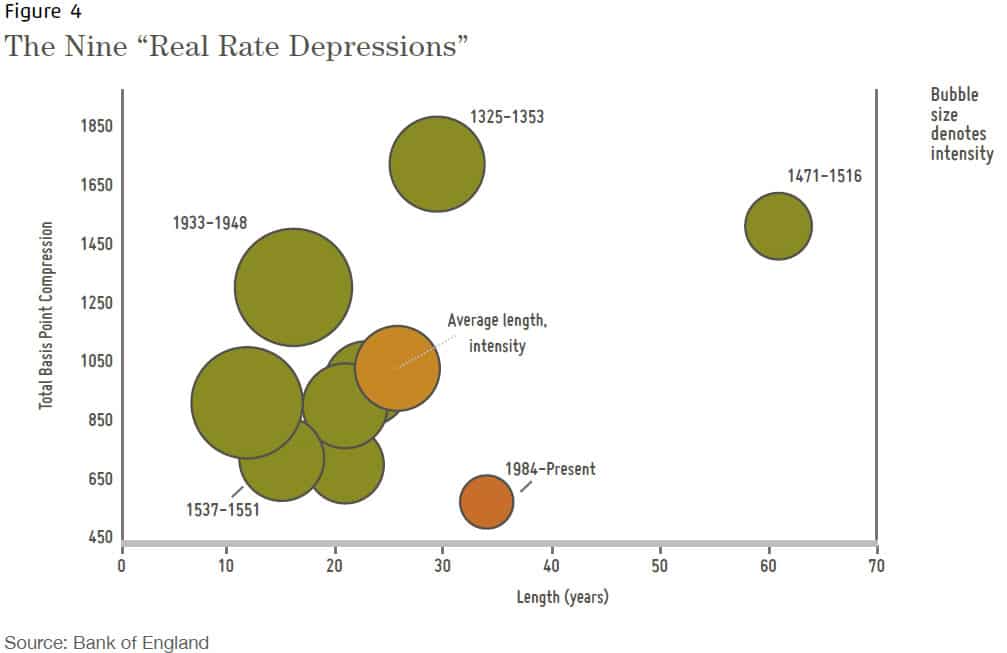

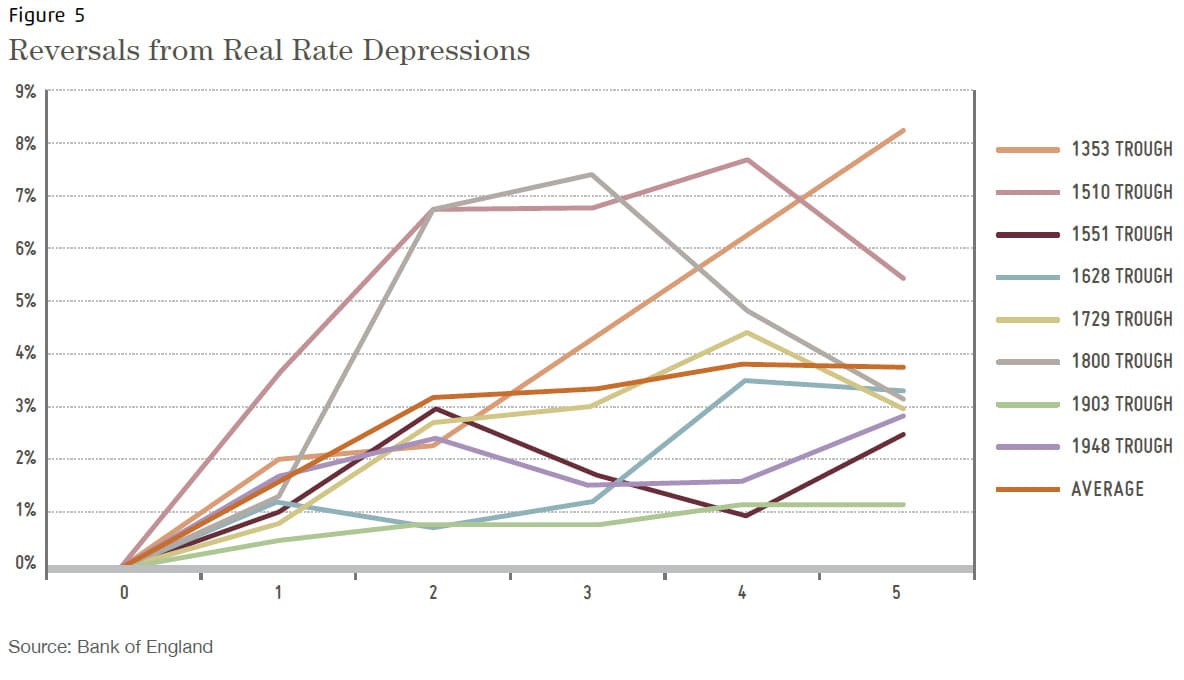

The current real rate depression (decline in real rates) in burnt orange, is the second longest on record. So, what typically happens afterwards? Professor Schmelzing continues: Most reversals to “real rate stagnation” periods have been rapid, non-linear, and took place on average after 26 years. Within 24-months after hitting their troughs in the rate depression cycle, rates gained on average 315 basis points, with two reversals showing real rate appreciations of more than 600 basis points within 2 years. Generally, there is solid historical evidence, therefore, for Alan Greenspan’s recent assertion that real rates will rise “reasonably fast”, once having turned.

In other words, the current 35-year decline in real rates is longer than average (26 years) and that this process reverses quickly after hitting bottom. ‘Non-linear’ refers to the path of the reversal being difficult to discern if you are living through it. The average increases in real rates during reversals is very significant, averaging 3.15% in the first 24 months. In the current environment, even a below average increase of 2.5% would badly rattle financial markets. In other words, investors would not be prepared for such a turn and will suffer. Unfortunately, hitting the trough, the point at which real rates start to quickly increase, is only knowable in retrospect. Figure 5 illustrates the average real rate increases following a trough.

Professor Schmelzing adds another observation to these periods: Most of the eight previous cyclical “real rate depressions” were eventually disrupted by geopolitical events or catastrophes, with several – such as the Black Death, the Thirty Years War, or World War Two – combining both demographic, and geopolitical inflections.

The insights I draw from this research is that the probability of a hard landing /crash is uncomfortably high. In retrospect, I was too early in my concerns about inflation (2016) although at the time inflation had picked up significantly and a new factor entered the equation; local governments, cities and states passing minimum / living wage laws of $15/hr.

In Mr Dalio’s view, there are very clear political risks on the horizon: …it is likely that there will be a battle over 1) how much of those promises won’t be kept (which will make those who are owed them angry), 2) how much they will be met with higher ta xes (which will make the rich poorer, which will make them angry) …

… there will be greater internal conflicts (mostly between socialists and capitalists) about how to divide the (economic) pie and greater external conflicts (mostly between countries about how to divide both the global economic pie and global influence).

Note that the promises referred to are social liabilities like Medicare, Social Security, healthcare, and pensions. The division of the economic pie refers to the current high level of income inequality, meaning the middleclass has been left behind. Why aren’t investors more concerned about these issues? After all, markets are supposedly forward-looking and take into consideration current and future risks.

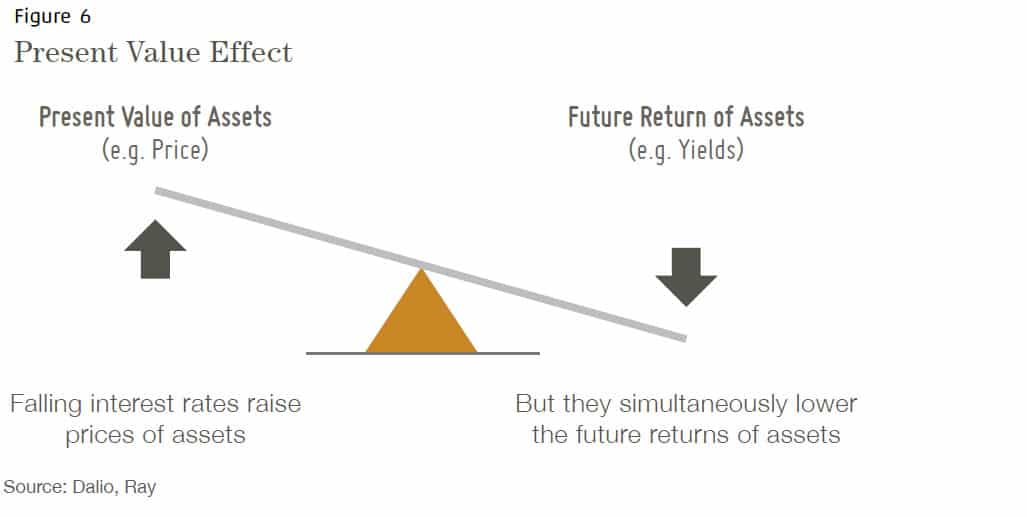

Mr. Dalio explains investor complacency in today’s environment: Thus far, investors have been happy about the rate/return decline because investors pay more attention to the price gains that result from falling interest rates than the falling future rates of return. The diagram below helps demonstrate that. When interest rates go down (right side of the diagram), that causes the present value of assets to rise (left side of the diagram), which gives the illusion that investments are providing good returns, when in reality the returns are just future returns being pulled forward by the “present value effect.” As a result, future returns will be lower.

In the near future, stocks and bonds could extend gains due to the present value effect, but future returns are dismal at these price levels. To earn better returns for your future, I am waiting for lower prices. I appreciate your patience with my approach, it’s not easy to be on the sidelines; half the investment world is taking short term profits on the demise of interest rates while the other half is wringing their hands over its implications.

Both BCA and Mr Dalio mention gold as a part of a diversification strategy.

Should MCS Clients be Invested in Gold?

During my career, I have witnessed a few boom/bust gold markets, starting in the early 1980s. My take away was it’s extremely difficult to make money in gold, and that gold is not a tru e long-term investment. The reason I say it’s not an investment is because it offers no income in the form o f rent, profits or interest. It costs money to store and keep it safe.

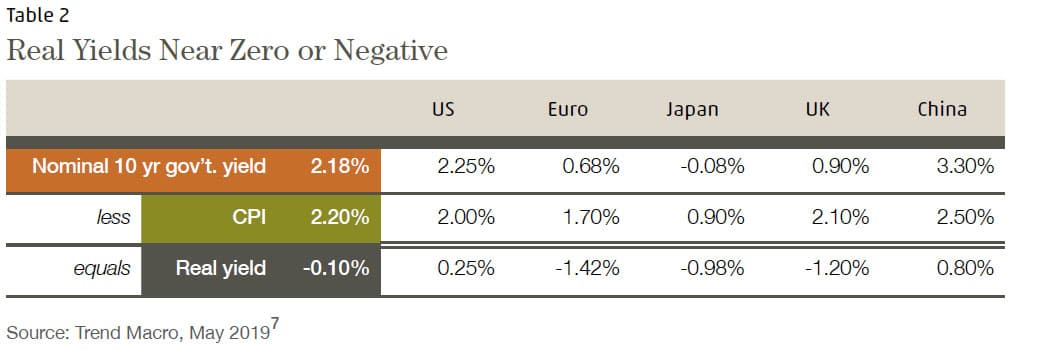

Gold is an alternative currency, and an ancient and universal one at that. There are long periods, measured in decades, when it can be a very poor investment. It performs poorly if real interest rates are rising and performs well if real rates are negative. The real rate is the nominal (actual) rate minus the inflation rate.

Today, real rates are negative or near zero in many parts of the world.

Therefore, a strong argument can be made for owning some gold in this environment provided real rates stay low or negative.

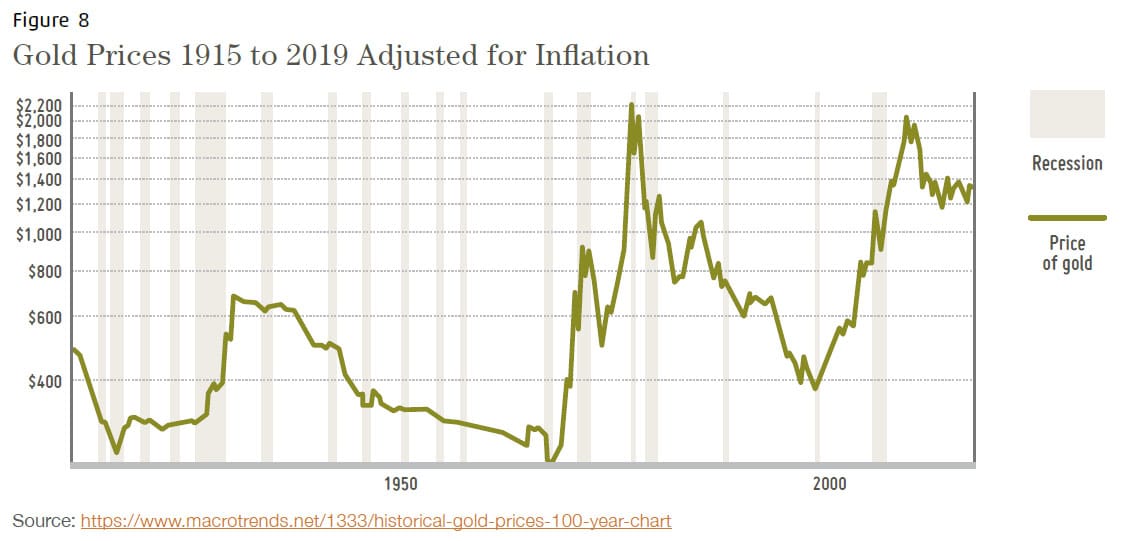

The Figure 8 shows Gold prices adjusted for inflation. Dark bands indicate recessions. Looking at the recession periods you can see that gold was volatile and didn’t necessarily protect investors except in the Great Depression 1929-1933 and the 1973-1975 recession.

The current negative and near zero level of real rates argue for owning some gold, with the caveat that gold is a tactical allocation rather than a buy and hold asset. Gold could perform well while the Fed is cutting rates.

On the other hand, should real interest rates rise in response to higher than expected inflation, US Treasury Bills (T-Bills) would be more attractive. T-Bills offer no loss of principal, are non-taxable at the state level, and their returns increase within 3 to 6 months as they mature and are reinvested at higher rates.

Bottom Line

Thirty-five years of falling real rates of return has convinced many professional investors that the outcome for the US will be like Japan and Europe, where central banks have pushed real rates of return down to combat sluggish economic growth. While those polices are proving less and less effective, the belief is that the zero or negative returns will persist indefinitely. This could certainly lead to a further melt-up in stock prices because bonds offer poor future returns.

Mr Dalio sees investor enthusiasm for stocks and bonds as the classic mistake of projecting the recent past into the future. Nevertheless, he believes that central banks will have little alternative but to expand upon current polices in an attempt to sustain economic growth. He recommends an allocation to gold to counteract the negative effects of these policies.

Seven hundred years of data on real rates of return tell a story that these periods of declining real yields (Real Rate Depression Cycles) have occurred throughout history. The cycle can reverse quickly after running its course. This cycle, at 36 years vs an average of 26 years, is the second longest on record and implies a reversal may be overdue. On the other hand, who knows how long? The sample size of 9 periods is a small one. Often, the bottoming out process coincides with significant catastrophes or geopolitical events tied to demographic changes.

Applying this to Today; One Scenario to Consider

The early, late stage of the Real Rate Depression Cycle sees increased efforts to further reduce real rates to maintain economic growth. Initially bond prices and stocks may gain on the ‘present value effect’ described by Dalio (and previously by yours truly, but perhaps not as cogently). However, pushing interest rates into negative territory is likely to fail. At some point, investors reject governments printing money to buy bonds supporting the debt expansion while keeping rates artificially low. These actions cause a loss of faith in bonds and ‘paper’ money. In response, gold gains in value as an alternative currency.

Until… the later stage when the Fed comes to its senses and, co nsistent with its mandate to promote stable prices (keep inflation around 2%) and past reversals of the cycle, real rates rise quickly to rein in inflation and preserve the value of the currency. The reversal from ‘free money for borrowers’ to ‘relatively expensive money’ unfolds in chaotic fashion (non-linear) over roughly two years, wracking financial markets. Gold gyrates wildly eventually falling in response to rising real rates.

I haven’t even touched on the potential social unrest that a clash between the haves, have nots, liberals, conservatives and a toxic presidency may engender. If you are concerned about dark days ahead, unrest often improves gold’s safe haven allure.

How do you invest in Gold?

There are many choices but among the easiest and most straight-forward is a buying a gold bullion, exchange traded fund. The price fluctuates directly with the value of gold. Gold mining stocks are problematic because they hedge their production and may not respond as you’d expect to increased gold prices. We (meaning you, the client, and I) should reflect on this.

I still have ambivalence about gold investment because timing in/out matters a lot to its success. It’s not a buy and earn income asset. Additionally, the investment needs to be 5% to 10% of the portfolio to begin to offer some diversification benefits. Here’s the math; A 5% position that increases or decreases 30% changes the portfolio value + or – 1.5%. A 10% position changes the portfolio value + or – 3%. Guessing at gold price downside vs upside, I’m thinking downside 33% / upside 100%. Finally, the tax treatment of gold gains and losses is not the same as stock and bonds. Therefore, the type of account; taxable or tax deferred (e.g. IRA) holding the gold investment should be considered.

My preferred strategy is to wait in relative safely near the sidelines and as a crisis unfolds buy income producing

assets at lower prices / higher yields. That said, if you would like to explore whether gold should be in your

portfolio, please send an email to michael@mcsfwa.com with ‘Gold’ in the subject line.

1MCS Family Wealth Advisors (MCS) consolidated client returns are dollar-weighted, net of investment management fees unless stated otherwise, include reinvestment of dividends and capital gains and represent all clients with fully discretionary accounts under management for at least one full month during the period. Individual client returns represent client discretionary accounts under management for the entire period – starting on 12/31/2017 and ending on 09/30/2018.These accounts represent 97% of MCS’s discretionary fee-paying assets under management as of 09/30/2018 and were invested primarily in US stocks and bonds (15% of client assets on 09/30/2018 were invested in tax-exempt municipal bonds). The Stock Index values are based on the S&P 500 Total Return Index, which measures the large capitalization US equity market. The Bond Index values are based on the Barclays Capital US Aggregate Bond Index, which measures the US investment-grade bond market. Index values are for comparison purposes only. The report is for information purposes only and does not consider the specific investment objective, financial situation, or particular needs of any recipient, nor is it to be construed as an offer to sell or solicit investment management or any other services. Past performance is not indicative of future results. 2https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-06-20/bull-market-saved-central-banks-now-risk-an-investorbacklash 3https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-06-27/liquidity-and-a-lie-funds-confront-30-trillion-wall-ofworry 4“Liquid Alts” is shorthand for “Liquid Alternative Investments.” Liquid Alts are mutual fund or ETFs that invest in non-traditional asset classes such as private businesses, venture capital, real estate partnerships, oil, precious metal commodities, crypto-currencies, art and antiques, agriculture land or loans. Although they can be traded on

a market, their liquidity has not been tested in a crisis situation. 5https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/paradigm-shifts-ray-dalio/ 6https://bankunderground.co.uk/2017/11/06/guest-post-global-real-interest-rates-since-1311-renaissanceroots-

and-rapid-reversals/ 7https://trendmacro.com/system/files/data-insights/20190530TrendMacroRealRates-49.pdf

Categories

2019 Second Quarter Newsletter & Outlook

The first half of 2019 was a drama involving the bond market anticipating a recession and the stock market assuming that the Fed would ride to the rescue by pushing interest rates lower. The Fed indicated a rate cut would be prudent to ensure continued economic growth; stocks continued to rally while bond holders remained wary of recession risks.

Through June 30, 2019 (if MCS clients’ investments were treated as one large portfolio including their cash), on average clients gained 3.34%1, after fees. For comparison purposes, the S&P 500 Total Return Stock Index (S&P 500) gained 18.54%, and the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index gained 6.11%. The range of MCS individual client returns was from a gain of 0.80 % to a gain of 7.25%. MCS results represent the downside of a defensive strategy; you don’t make as much as investors that took more risk. If that leaves you frustrated, let’s have a conversation; it’s easy to get more exposure to stocks.

As a money manager, a key part of my job is reading, reading and more reading to understand the world and what others think about it, and then to use that information to make the best investment decisions for my clients. I look for harbinger articles: articles that may have significant future implications but are currently an emerging or under-appreciated aspect in the economy or investments. Economic research reports play an important role in comparing the past and present trends and their future implications. This newsletter quotes liberally from these sources. I think it’s important for you to know that my concerns are shared and expanded upon by some of the world’s top investment managers. I feel that having concepts explained in a different way by someone else is conducive to better understanding.

In this newsletter, I’ll offer a summary of and comments on some of the best infor mation I’ve come across.

The Experts Don’t Agree… Even Within the Same Firm

I am a long-time subscriber to the Bank Credit Analyst (BCA), an investment newsletter that starts at around $20,000 per year. This independent economic research firm is like hiring a team of economists. Their work is very high quality.

This week, BCA published an overview of the diverging opinions within their organization about the direction of the global economy and their corresponding financial market recommendations. Table 1 below lists an edited summary of their positions. The lack of a clear consensus within this important economic research firm is indicative of the investment decision challenges in the current environment.

I have highlighted their recommendation on gold, which will be discussed later in this newsletter.

Comments from Other Asset Managers Supporting and Informing Our Investment Strategy

A Bloomberg article on 06/20/2019, “Bull Markets Saved, Central Banks Now Risk an Investor Backlash2,” highlights my concern about how low the world’s central banks have pushed interest rates. Other institutional investors also fear that Central banks have little or no room to lower interest rates further to rescue economies from the next downturn. The article’s authors, Ksenia Galouchko and David Goodman, state:

Their fear is that fresh stimulus, in the form of cheaper credit or even further bond-buying, won’t be enough to spark an uptick in chronically low inflation. Instead, it risks pumping up already pricey assets, potentially creating bubbles along the way.

“This reliance on central banks will take its toll on investors that take too much risk with their portfolios,” said Paul Flood, a multi-asset fund manager at Newton Investment Management, which oversees about 50 billion British pounds ($63 billion). “This will be a huge policy error that’s led to huge unintended consequences.”

The fear is that a US deflationary cycle could set in, similar to Japan’s since 1990. In essence, if the Fed halves interest rates from 2.5% to 1.25%, it will not have the same simulative economic impact as lowering interest rates from 5% to 2.5%. Stock market gains are increasingly based on financial engineering; relying on ultra-low interest rates and stock buybacks rather than improved company performance. Negative yields are designed to force borrowers out of safe assets by penalizing them for being conservative. Institutional investors see the potential for

a very bad ending to this cycle. Galouchko and Goodman continue:

The upshot is not all investors think policy makers have the ammunition to spur price growth laid low by the economic fallout of the financial crisis and still hobbled by structural obstacles like aging populations and rising debt.

Another Bloomberg article warns about the lack of liquidity in many investments. In “Liquidity and a ‘Lie’: Funds Confront $30 Trillion Wall of Worry.3” Annie Massa and Craig Torres write:

…the head of the Bank of England warned that funds pushing into a host of risky investments — in some cases, without investors fully understanding the dangers — have been “built on a lie.’’ Then the central banker, Mark Carney, spoke a word few policymakers use lightly: “systemic’’ — central bank-speak for the kind of risks that can cascade through markets, institutions and economies. Some $30 trillion is tied up in difficult-to trade investments, he noted earlier this year.

The Federal Reserve highlighted liquidity risk in bond and loan mutual funds in its May financial stability report, noting that bank loan funds purchase a full fifth of newly originated leveraged loans. “The mismatch between these mutual funds’ promise of daily redemptions and the longer time required to sell bonds or loans may be heightened if liquidity in these markets diminishes in times of stress,” the report said.

Liquidity is the ability to buy/sell at low cost and in high volume. I have written earlier about the liquidity risks in bond funds and the bond market. Liquidity risk becomes an issue in the same way that “Fire!” being yelled in a crowded theatre does; people get hurt trying to exit a bad situation. I routinely get emails or calls pitching investment products called ‘Liquid Alts’4. I believe the term ‘Liquid Alts’ is an oxymoron; the liquidity only exists if the market remains orderly.

Investment crises often start in the less liquid areas of the economy and quickly ripple their way into the more liquid financial markets. For example, the 2008 Great Recession investment crisis was triggered by a failure of the credit default swap, an alternative investment.

The final article I will mention here, Paradigm Shifts5, was written by Ray Dalio, Co-Chief Investment Officer & Co-Chairman of Bridgewater Associates, L.P. one of the world’s most successful hedge funds. It is a long article, and I encourage you to read it in its entirety.

In this article, Dalio expounds in detail on a long-held investment philosophy of mine – what starts out as a reasonable investment thesis eventually gives way to pure folly that must be understood and acted upon early to protect my clients’ wealth. Dalio calls these periods “paradigms”. For those of you who have been with MCS for more than 20 years, you will remember how I negotiated the Tech Bubble and the Great Recession investment crises. I believe we are at risk of another such crisis, and Dalio does an excellent j ob of describing it.

Dalio writes:

One of my investment principles is…Identify the paradigm you’re in, examine if and how it is unsustainable, and visualize how the paradigm shift will transpire when that which is unsustainable stops. … In paradigm shifts, most people get caught overextended doing something overly popular and get really hurt.

There are always big unsustainable forces that drive the paradigm. They go on long enough for people to believe that they will never end even though they obviously must end. A classic one of those is an unsustainable rate of debt growth that supports the buying of investment assets; it drives asset prices up, which leads people to believe that borrowing and buying those investment assets is a good thing to do. But it can’t go on forever because the entities borrowing and buying those assets will run out of borrowing capacity while the debt service costs rise relative to their incomes by amounts that squeeze their cash flows.

Another classic example that comes to mind is that extended periods of low volatility tend to lead to high volatility because people adapt to that low volatility, which leads them to do things (like borrow more money than they would borrow if volatility was greater) that expose them to more volatility, which prompts a self-reinforcing pickup in volatility.

Both high debt issuance in the corporate and government sectors and an extended period of low volatility exist now.

Dalio continues his article by proposing how the next paradigm shift might occur:

While I’m not sure exactly when or how the paradigm shift will occur, I will share my thoughts about it. I think that it is highly likely that sometime in the next few years, 1) cen tral banks will run out of stimulant to boost the markets and the economy when the economy is weak, and 2) there will be an enormous amount of debt and non-debt liabilities (e.g., pension and healthcare) that will increasingly be coming due and won’t be able to be funded with assets… Said differently, I think that the paradigm that we are in will most likely end when a) real interest rate returns are pushed so low that investors holding the debt won’t want to hold it and will start to move to something they think is better and b) simultaneously, the large need for money to fund liabilities will contribute to the “big squeeze.”

Like the Galouchko and Goodman article I quoted earlier, Dalio is saying that lower interest rates will stop working as a ‘go to’ solution to keep the global economies growing. At the same time, more debt will need to be sold to address increasing social liabilities like pensions and healthcare. The “big squeeze” is the mismatch between the need for more borrowing and the willingness of investors to lend. These situations are headline grabbing and chaotic. Mr. Dalio continues:

My guess is that bonds will provide bad real and nominal returns for those who hold them, but not lead to significant price declines and higher interest rates because I think that it is most likely that central banks will buy more of them to hold interest rates down and keep prices up. In other words, I suspect that the new paradigm will be characterized by large debt monetizations that will be most similar to those that occurred in the 1940s war years.

Here Mr. Dalio and I disagree. He suspects that bonds will experience modest losses, but interest rates won’t spike (creating large losses) as a result of these reflationary policies, the central bank will hold rates down by buying bonds. He references the 1940’s war years as an example of when this last occurred. This is certainly a possible outcome, however, I have serious concerns about this analysis. In the 1940s investors were favorably predisposed to buying bonds because:

In our current, less socially cohesive environment, investors may avoid buying more and more long-term bonds that yield nothing to pay for those liabilities. If investors don’t buy the bonds, government(s) will be forced to:

An alternative outcome to these events is higher than expected inflation, which reduces the cost of debt in real terms. The cost of debt is reduced because the bond payments are fixed, and interest and principal received in the future have less purchasing power. Higher than expected inflation could a mean significant increase in interest rates, assuming the Fed executes on its mandate to keep inflation around 2%. Such an interest rate increase would pull the rug out from under stock, bond, and real estate prices.

In either Mr Dalio’s outcome or mine, his investment recommendation is worth considering:

…those (investments) that will most likely do best will be those that do well when the value of money is being depreciated and domestic and international conflicts are significant, such as gold.

Wait, Aren’t Stocks an Inflation Hedge?

Stock investors have heard for years that stocks are a great inflation hedge. As a result, advisers and the financial press assure investors that owning stocks will protect them from inflation. Well, that’s true a lot of the time but not always. Stocks do terribly when inflation jumps unexpectedly and persists. As you can see in Figure 1, the high inflation environment of the 1970s produced dismal stock market returns, with the inflation adjusted return staying flat for almost 20 years from late 1968 until 1985 and again from 1999 to 2013. Stocks do exceptionally well when inflation is modest or declining.

The reason the data looks so favorable for US stocks vs inflation is because the data contains few high inflationary periods. During the Inflationary period itself, stock PE ratios can collapse, lowering stock prices significantly. Therefore, while stocks beat inflation in the long run, stocks get beat up during higher than expected inflationary periods. The circles and arrows in Figure 2 denote these very bad times for stocks.

Given that most of the investment community believes that inflation is not a threat, my view is that a much lower rate of inflation surprise (e.g. 2.50 to 3.00%) would be enough to cause PE’s to contract and prices to drop. The final article I will reference is this gem penned in November 2017 by Paul Schmelzing, a visiting scholar at the Bank of England from Harvard University. In “Global Real Interest Rates since 1311: Renaissance Roots and Rapid Reversals6,” he gives us a true long-term view. Although global inflation averaged at 1.09% over a 700-year period (much lower than I would have guessed), there is a ton of volatility around that average.

The current real rate depression (decline in real rates) in burnt orange, is the second longest on record. So, what typically happens afterwards? Professor Schmelzing continues:

Most reversals to “real rate stagnation” periods have been rapid, non-linear, and took place on average after 26 years. Within 24-months after hitting their troughs in the rate depression cycle, rates gained on average 315 basis points, with two reversals showing real rate appreciations of more than 600 basis points within 2 years. Generally, there is solid historical evidence, therefore, for Alan Greenspan’s recent assertion that real rates will rise “reasonably fast”, once having turned.

In other words, the current 35-year decline in real rates is longer than average (26 years) and that this process reverses quickly after hitting bottom. ‘Non-linear’ refers to the path of the reversal being difficult to discern if you are living through it. The average increases in real rates during reversals is very significant, averaging 3.15% in the first 24 months. In the current environment, even a below average increase of 2.5% would badly rattle financial markets. In other words, investors would not be prepared for such a turn and will suffer. Unfortunately, hitting the trough, the point at which real rates start to quickly increase, is only knowable in retrospect. Figure 5 illustrates the average real rate increases following a trough.

Professor Schmelzing adds another observation to these periods:

Most of the eight previous cyclical “real rate depressions” were eventually disrupted by geopolitical events or catastrophes, with several – such as the Black Death, the Thirty Years War, or World War Two – combining both demographic, and geopolitical inflections.

The insights I draw from this research is that the probability of a hard landing /crash is uncomfortably high. In retrospect, I was too early in my concerns about inflation (2016) although at the time inflation had picked up significantly and a new factor entered the equation; local governments, cities and states passing minimum / living wage laws of $15/hr.

In Mr Dalio’s view, there are very clear political risks on the horizon:

…it is likely that there will be a battle over 1) how much of those promises won’t be kept (which will make those who are owed them angry), 2) how much they will be met with higher ta xes (which will make the rich poorer, which will make them angry) …

… there will be greater internal conflicts (mostly between socialists and capitalists) about how to divide the (economic) pie and greater external conflicts (mostly between countries about how to divide both the global economic pie and global influence).

Note that the promises referred to are social liabilities like Medicare, Social Security, healthcare, and pensions. The division of the economic pie refers to the current high level of income inequality, meaning the middleclass has been left behind. Why aren’t investors more concerned about these issues? After all, markets are supposedly forward-looking and take into consideration current and future risks.

Mr. Dalio explains investor complacency in today’s environment:

Thus far, investors have been happy about the rate/return decline because investors pay more attention to the price gains that result from falling interest rates than the falling future rates of return. The diagram below helps demonstrate that. When interest rates go down (right side of the diagram), that causes the present value of assets to rise (left side of the diagram), which gives the illusion that investments are providing good returns, when in reality the returns are just future returns being pulled forward by the “present value effect.” As a result, future returns will be lower.

In the near future, stocks and bonds could extend gains due to the present value effect, but future returns are dismal at these price levels. To earn better returns for your future, I am waiting for lower prices. I appreciate your patience with my approach, it’s not easy to be on the sidelines; half the investment world is taking short term profits on the demise of interest rates while the other half is wringing their hands over its implications.

Both BCA and Mr Dalio mention gold as a part of a diversification strategy.

Should MCS Clients be Invested in Gold?

During my career, I have witnessed a few boom/bust gold markets, starting in the early 1980s. My take away was it’s extremely difficult to make money in gold, and that gold is not a tru e long-term investment. The reason I say it’s not an investment is because it offers no income in the form o f rent, profits or interest. It costs money to store and keep it safe.

Gold is an alternative currency, and an ancient and universal one at that. There are long periods, measured in decades, when it can be a very poor investment. It performs poorly if real interest rates are rising and performs well if real rates are negative. The real rate is the nominal (actual) rate minus the inflation rate.

Today, real rates are negative or near zero in many parts of the world.

Therefore, a strong argument can be made for owning some gold in this environment provided real rates stay low or negative.

The Figure 8 shows Gold prices adjusted for inflation. Dark bands indicate recessions. Looking at the recession periods you can see that gold was volatile and didn’t necessarily protect investors except in the Great Depression 1929-1933 and the 1973-1975 recession.

The current negative and near zero level of real rates argue for owning some gold, with the caveat that gold is a tactical allocation rather than a buy and hold asset. Gold could perform well while the Fed is cutting rates.

On the other hand, should real interest rates rise in response to higher than expected inflation, US Treasury Bills (T-Bills) would be more attractive. T-Bills offer no loss of principal, are non-taxable at the state level, and their returns increase within 3 to 6 months as they mature and are reinvested at higher rates.

Bottom Line

Thirty-five years of falling real rates of return has convinced many professional investors that the outcome for the US will be like Japan and Europe, where central banks have pushed real rates of return down to combat sluggish economic growth. While those polices are proving less and less effective, the belief is that the zero or negative returns will persist indefinitely. This could certainly lead to a further melt-up in stock prices because bonds offer poor future returns.

Mr Dalio sees investor enthusiasm for stocks and bonds as the classic mistake of projecting the recent past into the future. Nevertheless, he believes that central banks will have little alternative but to expand upon current polices in an attempt to sustain economic growth. He recommends an allocation to gold to counteract the negative effects of these policies.

Seven hundred years of data on real rates of return tell a story that these periods of declining real yields (Real Rate Depression Cycles) have occurred throughout history. The cycle can reverse quickly after running its course. This cycle, at 36 years vs an average of 26 years, is the second longest on record and implies a reversal may be overdue. On the other hand, who knows how long? The sample size of 9 periods is a small one. Often, the bottoming out process coincides with significant catastrophes or geopolitical events tied to demographic changes.

Applying this to Today; One Scenario to Consider

The early, late stage of the Real Rate Depression Cycle sees increased efforts to further reduce real rates to maintain economic growth. Initially bond prices and stocks may gain on the ‘present value effect’ described by Dalio (and previously by yours truly, but perhaps not as cogently). However, pushing interest rates into negative territory is likely to fail. At some point, investors reject governments printing money to buy bonds supporting the debt expansion while keeping rates artificially low. These actions cause a loss of faith in bonds and ‘paper’ money. In response, gold gains in value as an alternative currency.

Until… the later stage when the Fed comes to its senses and, co nsistent with its mandate to promote stable prices (keep inflation around 2%) and past reversals of the cycle, real rates rise quickly to rein in inflation and preserve the value of the currency. The reversal from ‘free money for borrowers’ to ‘relatively expensive money’ unfolds in chaotic fashion (non-linear) over roughly two years, wracking financial markets. Gold gyrates wildly eventually falling in response to rising real rates.

I haven’t even touched on the potential social unrest that a clash between the haves, have nots, liberals, conservatives and a toxic presidency may engender. If you are concerned about dark days ahead, unrest often improves gold’s safe haven allure.

How do you invest in Gold?

There are many choices but among the easiest and most straight-forward is a buying a gold bullion, exchange traded fund. The price fluctuates directly with the value of gold. Gold mining stocks are problematic because they hedge their production and may not respond as you’d expect to increased gold prices.

We (meaning you, the client, and I) should reflect on this.

I still have ambivalence about gold investment because timing in/out matters a lot to its success. It’s not a buy and earn income asset. Additionally, the investment needs to be 5% to 10% of the portfolio to begin to offer some diversification benefits. Here’s the math; A 5% position that increases or decreases 30% changes the portfolio value + or – 1.5%. A 10% position changes the portfolio value + or – 3%. Guessing at gold price downside vs upside, I’m thinking downside 33% / upside 100%. Finally, the tax treatment of gold gains and losses is not the same as stock and bonds. Therefore, the type of account; taxable or tax deferred (e.g. IRA) holding the gold investment should be considered.

My preferred strategy is to wait in relative safely near the sidelines and as a crisis unfolds buy income producing

assets at lower prices / higher yields. That said, if you would like to explore whether gold should be in your

portfolio, please send an email to michael@mcsfwa.com with ‘Gold’ in the subject line.

1MCS Family Wealth Advisors (MCS) consolidated client returns are dollar-weighted, net of investment management fees unless stated otherwise, include reinvestment of dividends and capital gains and represent all clients with fully discretionary accounts under management for at least one full month during the period. Individual client returns represent client discretionary accounts under management for the entire period – starting on 12/31/2017 and ending on 09/30/2018.These accounts represent 97% of MCS’s discretionary fee-paying assets under management as of 09/30/2018 and were invested primarily in US stocks and bonds (15% of client assets on 09/30/2018 were invested in tax-exempt municipal bonds). The Stock Index values are based on the S&P 500 Total Return Index, which measures the large capitalization US equity market. The Bond Index values are based on the Barclays Capital US Aggregate Bond Index, which measures the US investment-grade bond market. Index values are for comparison purposes only. The report is for information purposes only and does not consider the specific investment objective, financial situation, or particular needs of any recipient, nor is it to be construed as an offer to sell or solicit investment management or any other services. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

2https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-06-20/bull-market-saved-central-banks-now-risk-an-investorbacklash

3https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-06-27/liquidity-and-a-lie-funds-confront-30-trillion-wall-ofworry

4“Liquid Alts” is shorthand for “Liquid Alternative Investments.” Liquid Alts are mutual fund or ETFs that invest in non-traditional asset classes such as private businesses, venture capital, real estate partnerships, oil, precious metal commodities, crypto-currencies, art and antiques, agriculture land or loans. Although they can be traded on

a market, their liquidity has not been tested in a crisis situation.

5https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/paradigm-shifts-ray-dalio/

6https://bankunderground.co.uk/2017/11/06/guest-post-global-real-interest-rates-since-1311-renaissanceroots-

and-rapid-reversals/

7https://trendmacro.com/system/files/data-insights/20190530TrendMacroRealRates-49.pdf