THE RECENT STOCK market recovery has put many investors back into sleep mode when it comes to the risks they face. Many investors are like the frog in the familiar story – a frog dropped into boiling water will immediately jump out; but if placed in cold water that is slowly brought to a boil, the frog will be unable to distinguish the change in temperature and will remain immersed until it boils to death.

The recent changes in our financial world are not just cyclical – they are secular. Not only did consumers, investors, and businesses feel the burn in the past year’s crisis, but the much-touted recovery is a long, slow progression toward a future that is fundamentally different from what we have come to know. The past decade has brought a toxic environment for equity investments and has become indistinguishable from a “healthy” one. “Normal” is a relative term that describes an environment that is not too different from the one just experienced.

What keeps investors in the soup? Probably several things – strong belief in their investment philosophy, a reluctance to accept losses as final, and the desire for participation in a Hail Mary bull run that will make everything alright.

Many advisers and their clients have adopted the mindset of a losing gambler – they cannot walk away from the table out of fear that their next big run could begin at any time. A temporary improvement in their situation further reinforces the feelings that their luck will turn if they can just hang in there long enough. “Walking away from the table will lock in my losses,” the gambler thinks. “As long as I’m still playing, I have a chance to recoup.”

Successful investing is about having the ability to give up one’s most cherished beliefs if the weight of evidence suggests those beliefs are not congruent with reality. To survive and prevail depends on quick adaptation to the changed environment.

How many times must investors be hit over the head about their asset allocation before they figure out that rather than waiting for the pain to turn into a feeling of euphoria, a sane, rational person would change what they were doing? Many investors’ behavior is the equivalent of, “This will sure feel good when it stops hurting.”

The world has changed. Success in the new financial environment will come to those who adapt most quickly.

What Does the Much Talked About

Recovery Mean?

First, word on the street is about an expectation of an end to the recession – or more precisely, an end to declining GDP – in the third or early fourth quarter 2009. Interestingly, the July–August 2009 Harvard Business Review survey indicated that 69% of HBR readers thought the downturn wouldn’t end until mid-2010 or beyond.

Recovery is not about the stock market returning to the old highs or investors recouping their losses. The stock market run-up already has a third quarter 2009 recovery expectation embedded in it, so there will be little future stock appreciation unless the recovery is better than expected. I am in the camp that believes that stock prices have run too far too fast, given the uncertainties regarding the timing, duration, and robustness of the nascent recovery.

Real estate mania contributed to a strong economic recovery after the Tech Wreck of 2000–2003, yet the technology-heavy NASDAQ market index remains in the low 1,800s – a decline of over 60% from its peak of roughly 5,000 in the year 2000.

The point is that an overall economic recovery should not in any way assure investors that their own investments will recover if they simply stick to their plan, especially if that plan relies heavily on continued price appreciation.

Investors should reconcile themselves to the fact that all asset classes, and especially equity investments (stocks and real estate), are in the midst of an Era of Sub-Par Returns because the consumer, whose purchases represent 70% of economic activity, has been crippled by poor financial management and unreliable, self-serving financial industry advice.

Nevertheless, there is so much money committed to stocks as an asset class that some sectors will do OK; i.e., selected health care, energy, and strong niche businesses.

But here is the rub: Traditional investment strategies are likely to work poorly in the coming decade. Three reasons:

- Broad diversification and thus broad economic exposure may prove a poor investment strategy. Diversification is a double-edged sword if it puts you into poor investments that cancel out the performance of the few good ones. A highly competitive global economy characterized by low and halting economic growth will make stock investing really tough. Owning the market through low-cost index funds will prove “penny wise and pound foolish.”

- A long period of choppy, sub-par economic growth will force portfolio managers to trade more frequently – lowering returns. A vicious rotation between cyclical/defensive stock sectors and inflation/deflation bets will slap investors around both emotionally and economically.

- Investors, growing older and weary of risk with little return, will use rallies to exit the market – the tide of incoming stock investment that has characterized the past 25 years is slowly going out.

Asset allocation will be more important than ever, and more difficult – most advisers will continue to pound traditional assumptions about asset classes (square pegs) into triangular openings. The result will be busted portfolios. Our success at MCS Financial Advisors depends on continually assessing the macro economic environment (inflation, deflation, or goldilocks – not too hot, not too cold) and adjusting investments accordingly.

Will Inflation Spike?

The inflation scenario falls into two basic themes: 1) the dollar collapses and inflation skyrockets as foreign countries (like China) sell U.S. dollar assets because they no longer have confidence that the United States will pay off its increasing debt obligations, or 2) the U.S. Fed and Treasury consciously embark on a campaign to hike inflation to reduce the real cost of its debt obligations.

A significant portion of financial market participants are expecting an inflationary outcome. Their vigilance makes inflation less likely to become a big problem. Evidence of economic recovery quickly sends commodity prices and bond yields higher. These market reactions act as a counterweight to the possible runaway inflation scenario. Add a global excess of labor and production (service and manufacturing) capacity, and it is hard to build a case for sustained inflation of the 1970s–1980s variety.

There is a lot of uncertainty around how all the money borrowed by the Fed (especially that used to intervene during the 2008–2009 financial market collapse) is both repaid and removed from the banking system before becoming a potential stimulant for excessive inflation. If Japan is any example, it isn’t clear that the stimulus will even work, let alone cause runaway inflation.

The Problem that Refuses to Go Away

Residential real estate continues to be a significant drag on the economy. The government’s efforts to improve the housing market are not working. Cheap money isn’t doing it, first-time home buyer tax credits are not helping much, loan workouts don’t work, and banks are awash in deposits that they are not lending in any big way. Why? Because the real cure for this mess is waiting an uncomfortable amount of time (maybe 5–10 years) to let the supply of, demand for, and pricing of housing to come back into balance.

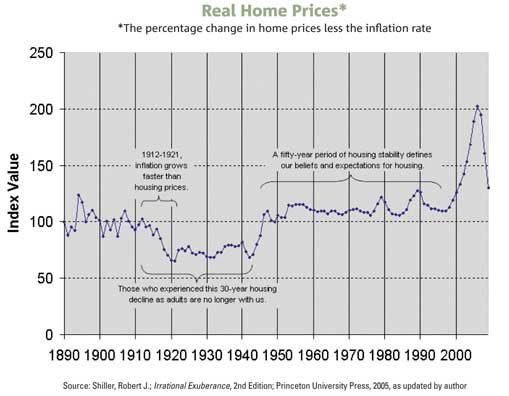

Robert Shiller, in his book Irrational Exuberance, compiled a history of housing prices that puts things in perspective.

Over the past 200 years, average home prices have not done much better than inflation. Our present-day expectations for home prices have been set by the post-WWII period, but our parents and grandparents lived a different story in the 30-year period before WWII. The illustration clearly shows how abnormally home prices have behaved over the past 10 years. As we approach the base value of 100 (keeping pace with inflation), the rate of price decrease should slow, but there is no reason to believe that prices will magically stay above the base value – they could easily continue to fall.

The stock market does not seem to appreciate this reality. The market rallied strong in March on the U.S. Treasury’s PPIP (Public–Private Investment Program) – the plan to sell banks’ toxic real estate loans and derivatives to an investor/government-owned fund. Stock market investors, thinking this was the Second Coming of the Resolution Trust (used two decades ago to bailout/liquidate the savings and loan industry), reacted with glee. Stocks rose 7% on the March 23 announcement.

The good news was that bank stock prices were lifted significantly on the assumption that PPIP would help put things right. Banks took advantage of their stock price increases to sell new shares, and now wish to use the share proceeds to redeem a portion of the government’s investment in them. Taxpayers should cheer.

The bad news is that the banks, by returning the government’s investment, have less capital to absorb future losses. Of course, they could probably go back to the well if there are no other alternatives.

Unfortunately, PPIP has been all sizzle and no steak. Banks remain encumbered by bad loans and risky, unmarketable securities, while lending at 15 large U.S. banks, which hold 47% of federally insured deposits, declined 2.8% in the second quarter.

Real estate – the underlying problem of the global recession – is worse than I expected. I know long-time readers of my viewpoint may find that hard to believe. The news about foreclosure prices is unambiguously horrendous.

Recent reports indicate that foreclosure prices in hard-hit areas are averaging 40% of the loan value – not of the purchase price (unless it was a zero-down loan). As The Wall Street Journal reported on July 9, the price meltdown is being fueled by bulk sales of repossessed properties by sub-prime mortgage securities holders. These sellers know that the first to dump inventory on the market get the best prices. The banks have been slower to recognize losses on foreclosures. This means that recovery rates on bank REO (real estate owned) will be lower than expected.

Economists cheered a report of increased housing sales in June, and an article in The Wall Street Journal reported that June home prices had risen after 34 straight months of decline. This was heralded as proof of a bottoming housing market. Here is the counterpoint: A day later The New York Times reported, “From June 2008 to June 2009, the number of American mortgages that were 90 or more days delinquent soared from 1.8 million to nearly 3 million, according to the realty research company First American Core Logic. During that period, the number of loans that resulted in the bank taking ownership of the home declined from 333,000 to 245,000.”

The recent “good news” on housing is not evidence of a bottoming or recovery. It is a miniscule bear market rally which will encourage real estate sellers to defer tough decisions and ultimately increase their losses. Significant downside risks remain. The 66% increase in mortgages that are 90 or more days delinquent from June 2008 to June 2009 is evidence of loss avoidance – a behavioral finance term that describes how investors will increase their risk taking to avoid the pain of loss.

All that is needed to magnify this crisis is a change in attitude by homeowners who are current on their payments yet owe more than the house is worth. Rather than struggle to pay off a home that is worth much less than the loan on it, they can make a rational economic decision – a strategic default. A June 2009 study entitled “Moral and Social Constraints to Strategic Default on Mortgages”* should keep the Fed up at night. The study seeks to answer the question, “What does it take for a mortgage holder to overcome the moral injunctions of defaulting on a home loan?” It found that mortgage defaults rise dramatically once home prices fall 20% below the outstanding mortgage balance. Additionally, moral injunctions against default break down when a borrower knows someone who has defaulted.

There is a growing risk that we could see Act II of the Banking Crisis. This would occur if the markets conclude that government monetary and fiscal policies are having limited success in getting the economy back on track. Such an event could push the stock market back toward its March lows.

Finally, California is becoming an early test case for reconciling the clash between the funding of government services (health care, education, social services, and public safety) and the willingness of voters/taxpayers to finance these societal benefits. Stay tuned!

Bottom Line

The economic bias remains toward deflation, for seven reasons:

- Consumer net worth continues to erode

- Consumer savings is increasing, so spending (the key to economic growth) remains muted

- Unemployment and underemployment will remain high; public sector unemployment is at the beginning of a dramatic increase as municipal budgets contract

- The contraction of credit is in the 3rd inning

- Most real estate markets are far from recovery

- Stimulus money is not stimulating

- Excess global industrial and labor capacity remains high

My strategy will continue to emphasize investment-grade income producing securities. We are working on identifying international non-dollar securities or commodities that would provide income and a hedge against a decline in the dollar.

*”Moral and Social Constraints to Strategic Default on Mortgages,” Preliminary versions, June 2009, by Luigi Guiso, European University Institute, EIEF, CEPR; Paola Sapienza, Northwestern University, NBER, CEPR; Luigi Zingales, University of Chicago, NBER, CEPR.